CONTENT

- CNHH at Congress 2025, George Brown College or virtual

- Annual general meeting

- Events

- News from members

- Archives news

- Common initiatives from members

- Blogs & talks published by the CNHH

- Welcome to new members

- Staying Connected

I. CONGRESS 2025 GEORGE BROWN COLLEGE

Monday June 2 from 15:30 to 17:00 in WFL-703:

Rethinking Vietnam: New Canadian Diplomatic, Defence, and Development

Perspectives on the Vietnam War Chair : Tim Sayle

- Brendan Kelly, Mission Impossible: Canadian Diplomacy and the Search for Peace in Vietnam

- Jean-Michel Turcotte, Cold War Theatre: The Official History of Canadian Military

Observers in Vietnam, 1954-1973

- Susan Armstrong-Reid, Claire Culhane: Humanitarian, Activist, or Anarchist?

CNHH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

Monday June 2, from 12: 00 to 13:30

The Annual meeting of the CNHH will take place on, in WLF – 531 or virtually at https://carleton-ca.zoom.us/j/6543041746 ) Jean-Michel Turcotte will be in the room, and Dominique Marshall will hold the virtual meeting. Please contact them for more information JEAN-MICHEL.TURCOTTE@forces.gc.ca or dominique_marshall@carleton.ca

- Two international visiting scholars will be our special guests: Jonathan Crossen (Finland) and Henrique Schlumberger (Brazil)

- We will discuss, among other things, possible theme for a 2026 roundtable, possible publication of a blog out of the 2024 panel on “Local histories of famine relief: food, (in)security, justice and nature at the village/micro level.”

II. EVENTS

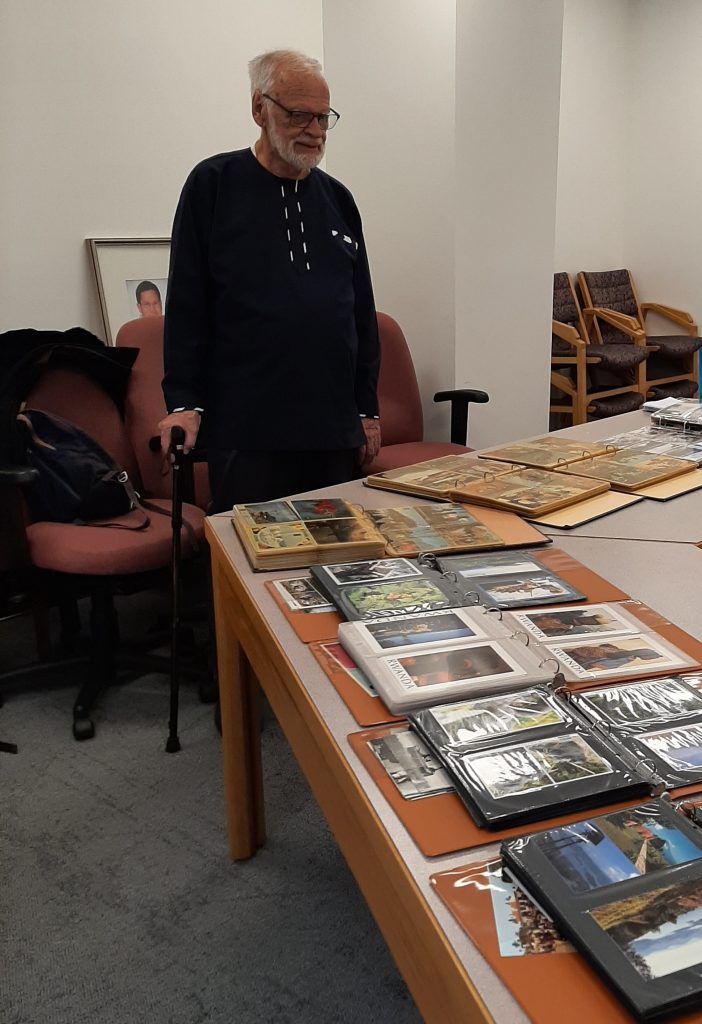

Tracing the History of Indigenous Women’s Internationalism: An Afternoon with Dr Jonathan Crossen

When: Wednesday June 25 from 1:00 to 3:00

Where: Lounge of the Department of History of Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, Paterson Hall 433.

Dr Crossen is Associate Professor at the Centre for Sámi Studies at UiT, the Arctic University of Norway & Visiting Scholar at Carleton University, Department of History

He will present his work on Indigenous Women’s Internationalism for 45 minutes. An exchange will follow, including a report on the research he is conducting in Ottawa this June on the international aid work of Inuit Circumpolar Council, and discussions on common interests.

The event is co-hosted by the Canadian Network on Humanitarian History (CNHH) and Carleton University Department of History. To know more, read Dr Crossen’s blog on the CNHH website: International cooperation between Indigenous peoples in the late twentieth century : inter-governmental undertakings and the history of Indigenous rights, May 5, 2025.

A virtual version will be streamed at this address: https://carleton-ca.zoom.us/j/6543041746

Please contact Dominique Marshall (dominque_marshall@carleton.ca ) for more information.

III. NEWS FROM MEMBERS

The CNHH is pleased to announce that a peer-reviewed article relating some of its members’ experiences engaging with communities and organizations around issues of humanitarian archives is now available to read in Issue 256 of the Revue internationale des études du développement. “Creating Development Archives Ethically from an Over-Developed Country” appears in a special issue dealing with development archives around the world. The article is available online and open access at: https://journals.openedition.org/ried/23482. Co-written by David Webster, Dominique Marshall, Chris Trainor, Sarah Glassford, and Eve Dutil, the article grew out of a thought-provoking roundtable sponsored by the CNHH at the 2023 conference of the Canadian Historical Association (CHA). See more details of the publication in a CNHH website blog post here.

Recent publications from CNHH member Jean-Michel Turcotte:

- Rising Above Captivity: The War Prisoners’ Aid of the YMCA, the United States and Global Humanitarian Action during the Second World War: The International History Review: Vol 0, No 0 – Get Access

- Coming soon! Canadian Military History: ““Your lads […] looked much like the reappearance of Jesus Christ to us” Canada, the ICCS and the release of US Prisoners of War in Vietnam,” Vol. 34, Issue 1 (2025), 35 p.

CNHH members Sonya de Laat, Valérie Gorin, Nassisse Solomon and Dominique Marshall successfully shared their exhibition “Artificial Global Health Images In and Before the Era of Artificial Intelligence” at McMaster University (February 2025), Carleton University (March-May 2025), and the Humanitarian Network and Partnership Week in Geneva, Switzerland (April 2025). Financial support provided through the CHA Collaboration Fund for 2024-2025 with colleagues Arsenii Alenichev, postdoctoral fellow at ITB Belgium, and Valérie Gorin from the Geneva Centre for Humanitarian Studies. The exhibition continues its travels, and will be next seen at Western University in the fall of 2025.

Building on the exhibition above, CNHH member Sonya de Laat successfully secured a SSHRC Connections grant to host a workshop at the Brocher Foundation in Hermance, Switzerland from 4-6 June 2025 on the topic of Artiificial Global Health Images. In this first of its kind workshop, co-hosts Sonya de Laat and Arsenii Alenichev (ITB Belgium) are bringing together photographers, aid practitioners, a diverse range of scholars (from media studies, histories of aid and international development, and bioethics), and aid communications specialists from the ‘global north and south’ to discuss what is at stake when artificial images become more prevalent, particularly when those images are reproducing historic wrongs and fakeries of different sorts (e.g., staging, racial pseudo-science). Workshop collaborators include CNHH members Valérie Gorin, Nassisse Solomon and Dominique Marshall.

IV. ARCHIVES NEWS

New CUSO Accession

Archives & Special Collections acquired tape recorded interviews that were intended, and used, as background for Ian Smillie’s 1985 book about CUSO, The Land of Lost Content. Some of the interviews were conducted by Peter Hoffman. The interviews cover various topics related to CUSO, so they provide additional context and background to the physical records ASC has related to CUSO generally.

Activist Archive, Canada (new online archive)

A new online archive is under construction on the history of environmental and peace organizations in Canada. Where major archives favour government documents and those of influential men, the Activist Archive Canada at https://activistarchive.ca/ will prioritize the records of non-governmental organizations by preserving them and making them accessible online. Crucially, the plan is to add descriptions and other metadata instead of simply uploading context-less scans.

First up is the Pacific People’s Partnership (PPP), a Canadian NGO marking its 50th anniversary. Based in Victoria BC, PPP is the only Canadian registered charity with a focus on the Pacific Islands. It works, in particular, to link Indigenous people in the Islands and in what is now Canada. With funds from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council, a team led by David Webster of Bishop’s University has digitized PPP’s paper records and made most of them available online at https://activistarchive.ca/pacific-peoples-parternship

The work involved digitizing paper records and photos, describing them using international archival system ISAD(G), and uploading them to the online archive, powered by the Access to memory (AtoM) system.

Next up is the Mae Sot Educational Project (MSEP), based in Sherbrooke, Quebec. MSEP has for 20 years been linking Canadian students and community members from Quebec’s Eastern Townships to refugees from Burma living in the town of Mae Sot, in Thailand.

Interested in contributing and being involved? Papers to share? Want to donate? Get in touch! dwebster@ubishops.ca

V. COMMON INITIATIVES FROM MEMBERS

Dominique Marshall received a three years SSHRC “Insight” Grant starting this Spring to write a monograph on the role of Oxfam in Canada from its foundation in the UK in 1943 to the unique role of the growing Oxfam confederation in the making of Canada’s transnational engagements with the global humanitarian regime since then. The program is based, among other things, on the existing work of archival collection done by several humanitarian veterans who are members of the CNHH. The provisional title is “UNEXPECTED SOLIDARITIES: THE ROLE OF OXFAM IN CANADIAN TRANSNATIONAL HISTORY 1943 – 2003.” The project includes a community-based archival component. Co-applicant and archivist, Chris Trainor, will help organise and make available the testimonies and documents gathered over the last 15 years, in close relation with officers of Oxfam Canada, who collaborated in the application. The team will use the grant to build a systematic depository of Oxfam materials at Carleton University, and build permanent bridges between this Fonds and similar collections, for the benefit of historians and NGOs.

VI. BLOGS & TALKS PUBLISHED BY THE CNHH SINCE THE LAST BULLETIN (June 2024)

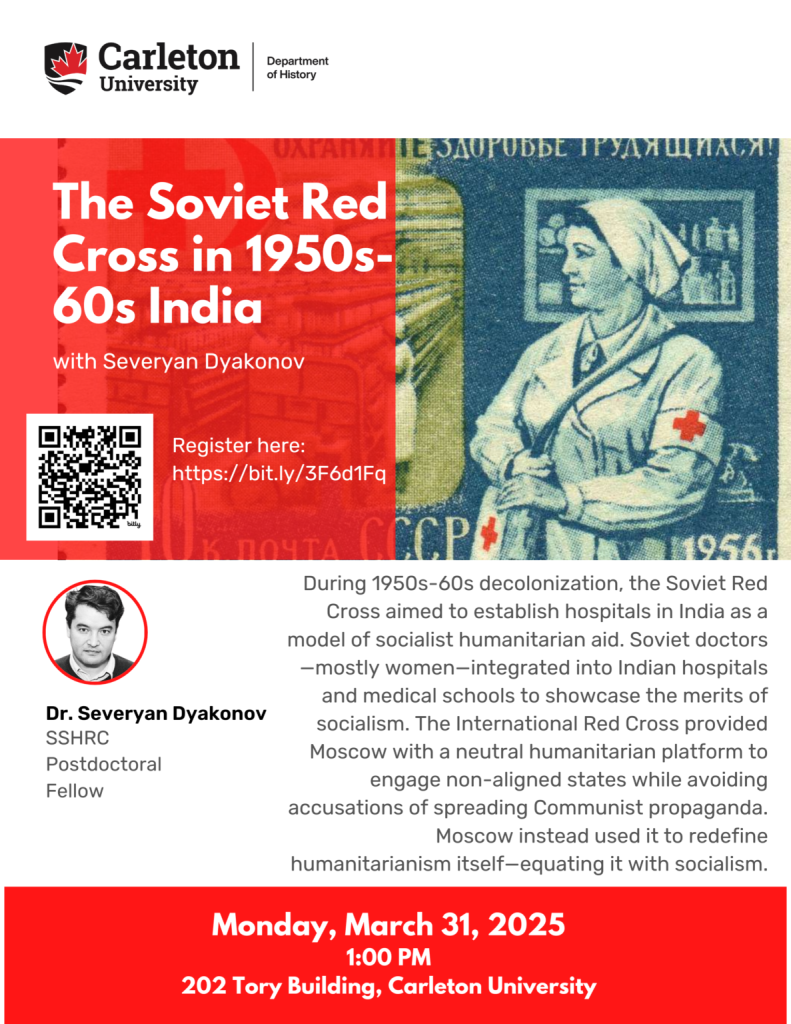

Severyan Dyakonov, Project on the International Red Cross Movement and the Cold War Divide, the 1940s–1980s, 22 May 2025.

Jonathan Crossen, International cooperation between Indigenous peoples in the late twentieth century : inter-governmental undertakings and the history of Indigenous rights, 5 May 2025.

Jill Campbell-Miller, Shocked, but not Surprised: The End of USAID in Historical Perspective. 18 April 2025.

Henrique Schlumberger Vitchmichen, Refugee Letters & the Ukrainian Committee for War Victims’ Relief in World War II, 2 April 2025.

Contribute!

If readers of the CNHH Bulletin would like to contribute to the “Essential Reads” series, or on any other subject relevant to our membership, please contact Sarah Glassford: Sarah.Glassford@uwindsor.ca . We would be thrilled to feature your reading recommendations, or your thoughts and experiences on other CNHH topics!

VII. WELCOME TO NEW MEMBERS

Peter Baltutis

Associate Professor, History and Religious Studies, St. Mary’s University

Email: peter.baltutis@stmu.ca

Dr. Peter Baltutis earned his Ph.D. in the History of Christianity/Theology from Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology in the University of Toronto. His doctoral dissertation was the first history of Development and Peace, the official international development organization of the Catholic Church in Canada and the Canadian member of Caritas Internationalis (a network of 162 national Catholic relief and development agencies working across the world). His research focuses on the historical and theological development of the Catholic social tradition in Canada and the role that faith-based NGOs play in international development and humanitarian aid. Currently, he is an associate professor of history and religious studies at St. Mary’s University in Calgary, where he also holds the Catholic Women’s League (CWL) Endowed Chair for Catholic Studies.

The full list of members is on the CNHH website.

VIII. STAYING CONNECTED

Social Media Connection Update!

The CNHH is moving to Bluesky, follow us at@aidhistory.bsky.social