by David Webster

When does the humanitarian impulse to provide aid and relief contribute to activism to promote human rights? When does it prompt avoidance of activism in favour of quietly enduring access to places and people in need?

This is one of the questions I am trying to answer in current research on relations between Canada and East Timor. Under Indonesian military occupation from 1975 to 1999, Canadian aid agencies tended to shy away from criticizing Indonesian actions in order to make sure they could deliver aid supplies. Humanitarian impulses dictated a quiet stance on human rights from a range of Canadian NGOs. But there was an early exception, in the work of Oxfam Canada.

Cover of AI Canada newsletter The Candle. From East Timor Alert Network papers and Library & Archives Canada.

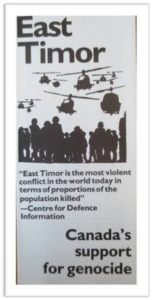

The small half-island country of East Timor was invaded by the army of Indonesia, the regional giant of Southeast Asia, at the end of 1975. Under Indonesian military occupation, more than 100,000 people died in what some observers called “tantamount to genocide.” Canada was among the many Western governments that backed Indonesian rule as “an accomplished and irreversible fact.” It wasn’t, of course: East Timorese fought on with guerrilla resistance, clandestine non-violent organizing, and diplomatic struggles, until they won the right to hold a referendum in 1999. After the vote went overwhelmingly for independence, an interim United Nations administration took over the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste formally regained its independence in 2002.

When are the beginnings of Canadian support for East Timor? Finding an answer to this sort of question requires interrogating both government and non-government archival sources. It’s only in 1983 that protest letters start to appear in the Timor file of Canada’s Department of External Affairs (after several name changes, External is now part of Global Affairs Canada). But it turns out that relying on the government records comes up with the wrong answer.

In fact, Canadian efforts to send humanitarian aid to East Timor began in 1975 before the Indonesian invasion, continued afterwards, and included efforts to lobby the Canadian government. These were not successful efforts – and there is no trace in the External Affairs documentary record – but they laid the groundwork for subsequent Canadian support for East Timor amongst humanitarian networks.

This early campaigning began through Oxfam Canada, which backed the aid work of Oxfam’s Australian affiliate, Community Aid Abroad, to get humanitarian supplies into East Timor. Specifically, CAA tried to send a ship with medical supplies shortly after Indonesia invaded East Timor on 7 December 1975. People were dying on Australia’s doorstep, and Australian humanitarian groups wanted to assist. They called on the global Oxfam network for support. Oxfam Canada made an immediate pledge of $10,000 and stood ready to offer more, director Helen Forsey-Conteras informed CAA.

The ship did not make it through. Instead, Australia’s government acted to prevent the ship from sailing and undercutting Australian government efforts to remain on good terms with Indonesia – regardless of the cost in Timorese lives. “Unfortunately the project to which part of your money was directed has come to a sudden and dramatic end,” CAA informed Oxfam Canada. “The medical supplies which we had purchased and organised to be shipped to East Timor were impounded by Australian navy vessels which arrested the boat and its crew on their way to Timor.”

CAA and other Australian humanitarian groups opened with a standard humanitarian logic: they wanted to help people in need. But the logic of what was happening in East Timor soon moved them into overtly political stances of opposition to Indonesian killings and other mass atrocities, and opposition to Australian government acceptance of Indonesia’s military occupation of East Timor. The same process happened within Oxfam Canada. “100,000 killed since Dec. 7, beginning of fighting. 1/6 of population,” Forsey-Conteras wrote in her notes on a phone strategy session with CAA. She added that “Austr[alian] business community passed resol’n that govt should stop oppos’n to Indonesia among NGOs – danger of info flow.”

Here were the lines of debate: business and government on one side, seeking to avoid headlines about mass killings; humanitarian groups on the other, trying to get the word out and alter government policy. Given this, it’s perhaps not surprising that Oxfam’s efforts are not recorded in the Canadian Department of External Affairs file for East Timor.

Oxfam Canada and Oxfam Quebec did try (without success) to shift the Canadian government’s policy of silence and abstention on the occupation of East Timor. Forsey-Contreras contacted other groups. Oxfam Canada lobbied the government – as did the director’s father, Senator Eugene Forsey, who seems to have provided advice. (Oxfam documents refer to him as “Dad.” I’m grateful to John Foster for confirming who “Dad” was, in this case.) The campaign also involved Oxfam Quebec, which in a letter to External Affairs minister Allan MacEachen deplored the way most Western governments were “washing their hands” [s’en lavent les mains] of the East Timor situation.

Oxfam’s campaign was abortive, with no apparent effect on Canadian government policy. External Affairs ignored groups like Oxfam, and did not start to pay much attention to letters from the public until the formation of the Nova Scotia East Timor Group in 1985, a campaign by Amnesty International launched in 1985, actions by the Ottawa-based Indonesia East Timor Programme starting in 1986, and finally the creation of a national East Timor Alert Network backed by Canadian churches in 1987. But the beginnings of Canadian solidarity for East Timor, it turns out, go back to 1975.

What I draw from these materials is that humanitarianism and the urge to solidarity with an oppressed people intertwined. This is a common phenomenon, but suggests that aid organizations are one more group that needs to be written into the story of Canadian action for human rights on East Timor. Second, there is much more going on than the government files reflect. To write a full history of Canadian interactions with East Timor – as I’m trying to do this year – requires looking at government and non-governmental organization records, with many of the latter found in unexpected places. Third, the story can’t be written from NGO files alone – the government documents are a good indication that no one was listening to Oxfam Canada in 1976, but officials in Ottawa were listening keenly to the pressure that began in the 1980s, and by the 1990s felt compelled to respond to it. But rights groups picked up on the same sort of language used in the earliest Oxfam-authored letters. There was a legacy: Oxfam’s lobby shaped later lobbying efforts.

What I draw from these materials is that humanitarianism and the urge to solidarity with an oppressed people intertwined. This is a common phenomenon, but suggests that aid organizations are one more group that needs to be written into the story of Canadian action for human rights on East Timor. Second, there is much more going on than the government files reflect. To write a full history of Canadian interactions with East Timor – as I’m trying to do this year – requires looking at government and non-governmental organization records, with many of the latter found in unexpected places. Third, the story can’t be written from NGO files alone – the government documents are a good indication that no one was listening to Oxfam Canada in 1976, but officials in Ottawa were listening keenly to the pressure that began in the 1980s, and by the 1990s felt compelled to respond to it. But rights groups picked up on the same sort of language used in the earliest Oxfam-authored letters. There was a legacy: Oxfam’s lobby shaped later lobbying efforts.

Relevant Oxfam documents appear in my recent history in images recently produced with support from the Indonesia and Timor-Leste Studies Committee of the Association for Asian Studies, https://canadatimor.wordpress.com/

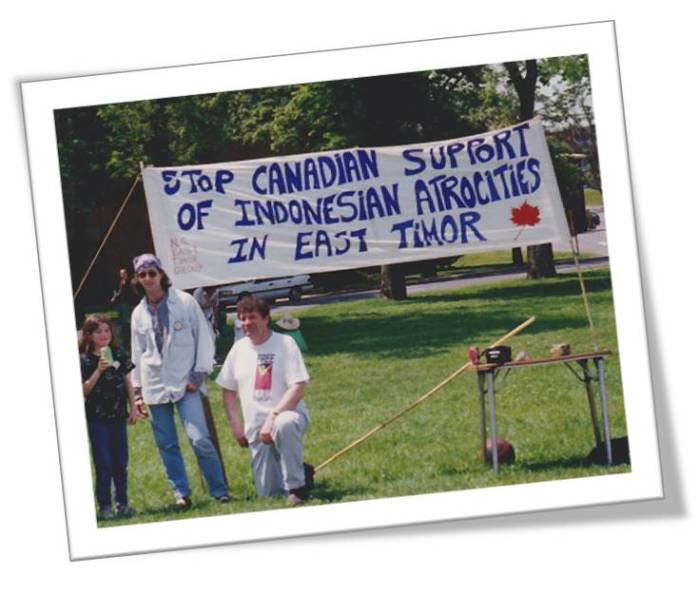

Featured image (at top): NSETG literature table and banner showing, Halifax. All images courtesy of Canadian Solidarity with East Timor, used with permission of the author.

On the project: At its 2017 conference, the Association for Asian Studies launched an initiative to promote Timor-Leste (East Timor) studies in North America. As part of that initiative, David Webster presented a photographic exhibit on the history of Canadian human rights activism in solidarity with East Timor, linked to the 30th anniversary of the founding of the East Timor Alert Network/Canada (ETAN). Webster previously arranged the donation of ETAN’s papers to the McMaster University Archives, where they have been used by researchers in Australia and elsewhere. The photo exhibit is also available online at https://canadatimor.wordpress.com/https://canadatimor.wordpress.com/

David Webster is an associate professor of History at Bishop’s University and currently vice-president of the Canadian Council for Southeast Asian Studies. His first book was Fire and the Full Moon: Canada and Indonesia in a Decolonizing World (UBC Press, 2009). He is currently writing a book on Canadian interactions with Timor-Leste (East Timor) from 1975-99 based on government and non-government sources.

0 Comments

1 Pingback