by Peter Ludlow, PhD

In 1928, facing political marginalization, outmigration, rural abandonment, poverty in coastal communities, and social unrest in the colliery towns of Cape Breton Island, St. Francis Xavier University (St. F.X), the college of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Antigonish, Nova Scotia, organized an Extension Department. Uncertain of success, and with few financial resources, Extension launched a program of study clubs, cooperatives, and credit unions that would ultimately be celebrated globally as the “Antigonish Movement.” While clergymen like Monsignor (Msgr) Moses M. Coady (1882-1959) and Father (Fr) James J. Tompkins (1870-1953), garnered most of the period headlines, the Antigonish Movement was unquestionably a vehicle for the Catholic laity, and most especially women, to resolve their own economic problems and become “masters of their own destiny.”

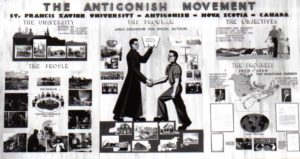

Period poster explains the concepts of the St. F.X. Extension Department (credit to Antigonish Diocesan Archive)

Championing adult education and community organization in a region that was plagued by poverty and outmigration was a challenge. Yet, by the late 1930s, miners had organized credit unions and libraries, fishermen opened modern cooperative lobster canneries, and home economics was taught throughout the countryside. While the Antigonish Movement was a product of Catholic social teaching, especially the idea of subsidiarity, it was not long before Protestants became involved both in study clubs and within its general leadership. So, while identified closely with the local Catholic Church (Pope Pius XI sent a special commendation in 1938), by the 1940s the movement had spread to numerous communities throughout the Maritime Provinces. It had also begun to attract the attention of journalists, academics, and writers, many of whom were often more interested in uplifting people than documenting facts.

By the early 1950s, while fieldworkers continued their work in communities like Inverness County, the Catholic Church turned its gaze toward Latin America. Facing poverty, and fearful of communism, bishops in countries like Panama and the Dominican Republic looked to the Maritime Provinces for solutions. By 1956, Extension leaders like Alexander Fraser Laidlaw (1908-1980), who had served as assistant director since 1944, took their experiences organizing cooperatives in small eastern Nova Scotia parishes like Heatherton, Judique, and Havre Boucher to India under the Colombo Plan (a Commonwealth strategy for Co-operative Economic Development in Southeast Asia). In the meantime, often in collaboration with the Scarboro Foreign Mission Society, priests and women-religious from the Maritime Provinces went south to organize cooperatives in countries like Puerto Rico. Unlike traditional missionaries, interested purely in conversion, these cooperators took “their St. F.X. techniques along with their liturgy.”[1]

It was not long before communities in Latin America began to send eager students back to the St. F.X. campus to witness the Antigonish Movement first hand. While there, the economic and social problems of countries like Cuba and Venezuela were debated with as much passion as those of Canso, Christmas Island, and Whitney Pier had been decades earlier. Through the United Nations Food and Agricultural Program, Extension’s leadership regularly toured Latin America and spoke at conferences. Priests like the Sydney native Fr George Topshee (1916-1984) offered intensive ten-day short courses for directors of credit unions and cooperatives in Ciudad Trujillo (now Santo Domingo), Dominican Republic, while other priests gave similar programs in Brazil.

By the mid-1950s, the quiet leafy college town of Antigonish had taken on a distinctly international character. In 1957, Scarboro House was opened to support those missionaries studying Extension strategies at St. F.X., and to help recruit local vocations. When Pope John XXIII formally asked Bishop John R. MacDonald (1891-1959) to focus on exporting the principles of the Antigonish Movement to countries like Cuba, the prelate soon “talked nothing but Latin America.”[2] Speaking of the “Antigonish obligation,” plans were hastily made for an “International House for Priests,” to train both clerical and lay cooperators. When formally established in December 1959, it was named for the original director of the St. F.X. Extension Department, Msgr Moses Coady, who had died only months previously.

Yet, while the St. F.X. Extension Department had worked primarily in the small rural communities of the Maritime Provinces and had often struggled with funding, the new Coady International Institute brought the university world-wide prestige and had access to greater financial resources. Consequently, when the Coady Institute secured a large donation from Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston for a beautiful new on-campus building, the director of Extension, Fr John Allan Gillis (1911-1973), desperately scrambled to make the new Institute an “extension of Extension.” Yet, underestimating the support both at St. F.X. and within the Diocese of Antigonish for an international arm of the Antigonish Movement, Fr Gillis was quickly replaced by a more accommodating clergyman.

Bishop John R. MacDonald walking to the St. F.X. Convocation in 1958 with Dr. Binay Ranjan Sen (1898-1993), head of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Sen was receiving an honorary degree (credit to Antigonish Diocesan Archive).

Exporting the ideas and strategies of the Antigonish Movement to communities across the world, gave the people of eastern Nova Scotia great satisfaction. Yet, the tension between local development (St. F.X. Extension Department) and international development (Coady International Institute) was present from the beginning. While Msgr Coady had unquestionably supported the idea of an international program before his death, as his name was synonymous with local development, many people confused the two organizations (this remains a problem today). Moreover, as more international students arrived on the St. F.X. campus, and news of the Institute’s global endeavours made headlines, people began to wonder if the university still cared about the local economy.

Moreover, while the early achievements of Extension were embedded in the psyche and historical memory of eastern Nova Scotia, the development of the Coady International Institute came as the department struggled to maintain its usefulness. At a time when the State was beginning to assert itself within the regional economy, many of the cooperative organizations that Extension had “birthed” no longer required its direct involvement. Organizations like the Nova Scotia Credit Union League, for example, were now capable of running its own affairs. So, as global communities were employing the techniques of Antigonish to solve their economic problems, in eastern Nova Scotia Extension seemed to be waning.

While the organizations were separate entities, from the beginning it was clear that university administrators would have to manage the needs of the Coady International Institute against local expectations for the Extension Department. In 1973, Fr Topshee, a hybrid of sorts, who had worked among the Cape Breton coal miners as well as “agricultural rehabilitation” teams in southern Africa, was given charge of both portfolios. Yet, by the early 1980s, the work proved too demanding and the organizations were formally divided once more. Importantly, while the Coady International Institute had the freedom to alter and diversify its work, when Extension directors changed program directions in the 1980s and 1990s, it brought mostly frustration from a community whose historical memory demanded an economic response similar to the 1930s. In other words, while the Coady International Institute was free to chart a modern course based upon the principles of the Antigonish Movement, the Extension Department was trapped by its history. While the Coady Institute had been the “international arm” of Antigonish, by the mid-2000s, one Extension director argued that the solutions to the economic woes of eastern Nova Scotia might actually be found within the global community. On a campus like St. F.X., where the ghosts of those early cooperators loom large, that was a difficult message.

While there are few places where local and international development are as intertwined as Antigonish, there are still tensions over governance, memory, and authenticity. Moreover, while St. F.X. appears committed to both organizations, the wolf is never far from the door. Extension is now the responsibility of the University Vice-President and Director of the Coady International Institute, and while they have no involvement whatsoever in the cooperatives and credit unions of the past, they are still working to support to a region that struggles economically and a community that continues to export its children to other parts of Canada. More recently, the Coady International Institute has faced a funding deficit, and has struggled to retain staff among a flurry of negative media coverage.

Yet, while these two veritable institutions continue with their own programs and agendas, the shared legacy of the Antigonish Movement will ensure that they remain tied very closely together.

[1] See The Casket, 16 April 1959. The diocesan newspaper ran a full page noting how the Antigonish Movement had a “Global Influence.” [2] Fr Hugh John MacDonald Interview, 9 October 1964, Antigonish Diocesan Archive, Peter Nearing Papers, Series 1, sub-series 1, folder 20. Fr Peter Nearing’s papers reveal the great responsibility that the Church in eastern Nova Scotia felt for the people in Latin America. See Peter A. Nearing, He Loved the Church: The Biography of Bishop John R. MacDonald, Fifth Bishop of Antigonish (Antigonish: The Casket, 1975).

Peter Ludlow is an adjunct professor of Catholic Studies at St. Francis Xavier University and president of the Canadian Catholic Historical Association. An expert on the Antigonish Movement, his first book, The Canny Scot: Archbishop James Morrison of Antigonish, was published by McGill-Queen’s university Press in 2015. He can be reached at pludlow@cchahistory.ca and @PLudlowhistory on Twitter.

Enjoyed the blog and the book. I would like to learn more. I was also hoping to hear your analysis and commentary on how the more recent history of Extension repeats itself or takes a departure from the past – of its role in local economy and society, relationship with the Institute, Continuing educations, university and the town/county… Will look forwrad to.