Immigrants and Refugees: today’s global debate and its rich historical roots

By Sandrine Murray

By Sandrine Murray

Ph.D. candidate Teuntje Vosters of the Netherlands visited Carleton University in November to discuss a historical persepctive of migration management and refugees

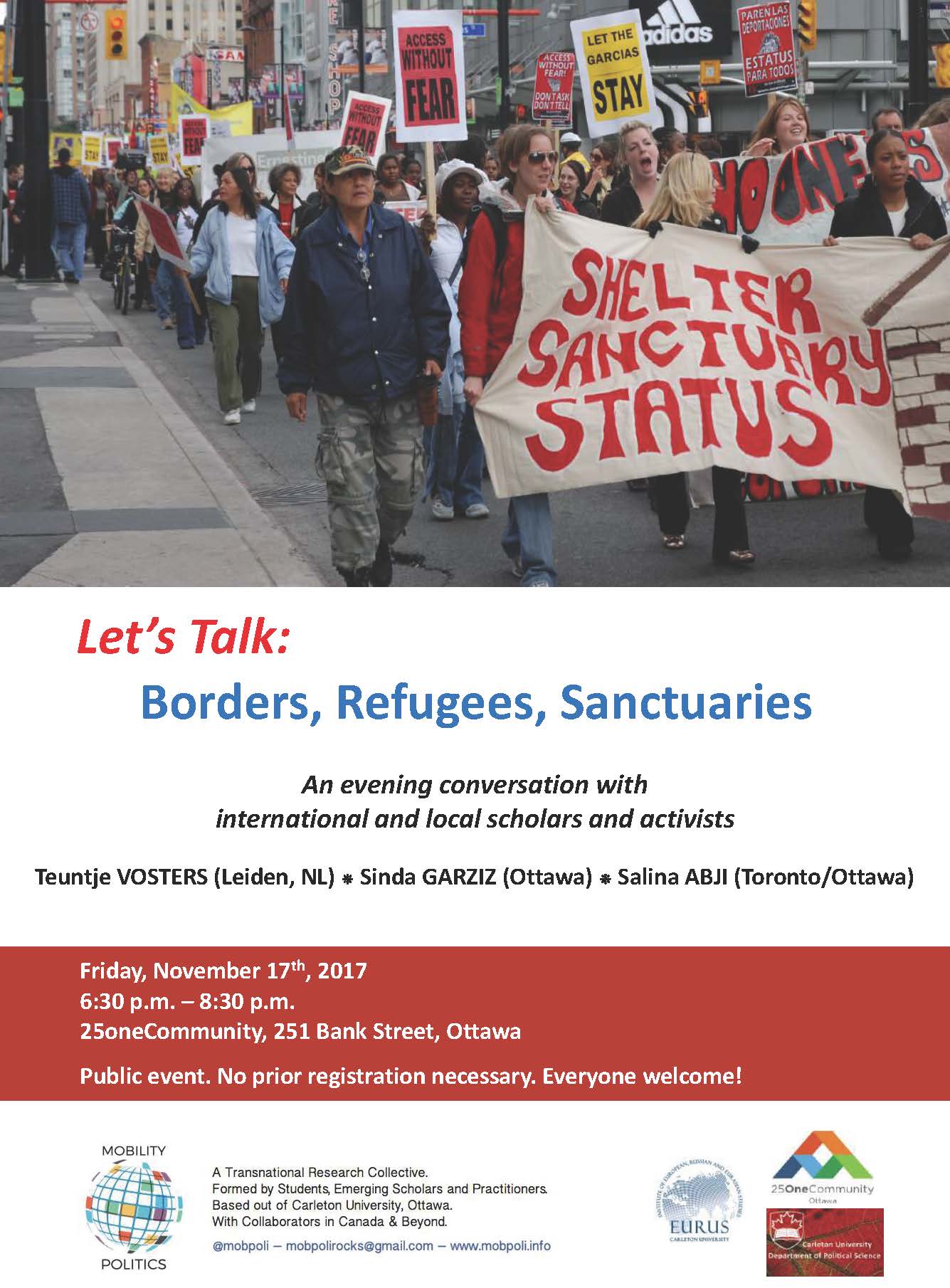

On Nov. 17, Carleton University hosted an evening conversation with international and local activists. Sinda Garziz, from Ottawa, Saline Abji, from Toronto, and Vosters.

Her visit coincided with a growing global concern on those very matters. A graduate student of Leiden University, her research on NGO and refugee policy is supervised by Professor Marlou Schrover and Dr. Irial Glynn. Vosters received the Social Science History Association’s award to attend a conference in Montreal, which brought her to Canada.

She also spoke to Carleton undergraduate students in Dr. Dominique Marshall’s class HIST3813A, “Problems in Global and Transnational Histories” and in dr. Martin Geiger’s classes PSCI 1501, “Migration Politics” and PSCI 4610 “Politics of Migration Management.”

In 2016, Donald Trump’s promise to build a wall on the southern and northern borders of the United States seemed inconceivable, perhaps a little ridiculous.

However, it successfully placed immigration to the forefront of current political debate. His anti-immigration stance, further exemplified by his targeting of sanctuary cities, received strong backlash from his opponents.

Responding to American rhetoric, Canada’s sanctuary city movement grew in early 2017. A sanctuary city is meant to grant illegal immigrants access to services without fearing deportation. Mayor John Tory reaffirmed Toronto’s status as a sanctuary city on Jan. 31. It was the first Canadian city to become one in 2013. But some activists say the actions of the Toronto City Police, like their presence near women’s centres to find undocumented immigrants, prove the contrary.

In Canada, curiosity surrounding border security was depicted—some say exploited— in shows like “Border Security: Canada’s Front Line,” which aired from 2012 until 2016. A watchdog found privacy laws were breached when an illegal immigrant, who has since then been deported back to Mexico, was filmed without his consent.

It was subsequently cancelled.

The world of migration and its vast terminology: immigrant, alien, migrant, refugee, asylum-seeker… are important parts of history, both in Canada and the world. A treasure trove of information exists in a study of its international implications.

Humanitarian history comes into play as individuals and groups work to shape society, striving for policies they believe are required. For people trying to leave their homeland for a better life, discussions in academia are part of the process for their successful crossing of borders.

Dr. Martin Geiger, a Carleton University professor of human migration and mobility, created a research website joining together researchers, emerging scholars and practitioners from around the world to discuss matters of cross-border flow and international migration.

Canada’s immigration vetting process is good, as Garziz explained. An article in the New York Times on June 28, 2017, boasted the headline: “Canada’s Ruthlessly Smart Immigration Policy,” praising its merit-based system. Trump apparently wants to mimic the Canadian system.

But for people bypassing the immigration process, life in Canada proves a very different challenge. The discussion pointed out Canada’s failures in its response to these undocumented immigrants.

For example, the incarceration rules for an undocumented immigrant mean children often find themselves in prison. Because they’re classified as “visitors,” they are technically free to come and go. But inevitably, they are dependent on their parents, so they stay with them.

A report published in early 2017 by the University of Toronto determined more than 200 Canadian children were held in immigration detention centres in recent years, though some work has been done to change that reality.

Teuntje Vosters’s research goes elsewhere to look at the immigration situation: in European refugee history. Just as in recent years, large numbers of refugees have been seeking asylum in Europe over the course of the 20th century. Her research analyses preceded refugee crises and the development of international refugee policy over time.

NGOs, Vosters argues, have had a crucial role in the shaping of refugee policy. Her research question asks, “To what extent have NGOs influenced international refugee policies, and if so, how and why?’

In a current climate of debate, a look at the global stage might prove insightful. Even Trump’s isolationist, America-first outlook did not stop him taking note of Canada’s own immigration framework.

In her research, Vosters focuses on four key moments. These moments are periods of crisis, discussion, and or change in policy. In 1922, the Nansen Passport was created for stateless refugees from Russia. Thanks to pressure from the Red Cross, 65 states signed. The Evian Conference in 1938 discussed the fate of refugees, including 32 countries and 63 private and voluntary organizations coming together. Twenty-six NGOs were actively involved in drafting the Refugee Convention put forward in 1951, which defined the term “refugee.” In 1967, that same convention became more global, when time and geographical limitations were removed.

These events help explain the international cooperation concerning refugees, starting only after the First World War (though NGOs have existed before.) Her study includes organizations such as the Red Cross and Save the Children.

One might easily see how when speaking of refugees and migration management, NGOs come into play to shape policy; NGOs had a vital role in determining refugee policy at some moments, and less so during others What is more complex and less well known is why NGOs had such a major influence. Vosters’s research demonstrates how their influence on refugee policy cannot only be explained only by looking at the well-known structural factors such as (among others) economic crises and (geo)political power relations. The organizations’ own activities, tactics and strategies also influenced their impact. These internal NGO factors, that show a fair share of NGO agency, are under study in Vosters’s research.

Author: Sandrine Murray is an RA for the CNHH and a fourth-year journalism and history student at Carleton University.

0 Comments

1 Pingback