Fourteenth Bulletin of the CNHH, November 2023

With a goal of having at least two bulletins a year, this is the second bulletin of 2023. Please continue sending updates as we prepare for the next bulletin for May 2024.

CONTENT

- CNHH at Congress 2024, York University or virtual

- Round table on Local histories of famine relief – still time to join the panel

- Annual general meeting – Save the approximate date

- News from members

- Archives news

- Common initiatives from members

- Blogs & talks published by the CNHH

- Welcome to new members

I. CONGRESS 2024 McGILL UNIVERSITY

CNHH ROUNDTABLE, ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING & OTHER NEWS

- Roundtable: “Local histories of famine relief: food, (in)security, justice and nature at the village/micro level”

- Format: Roundtable, hybrid format (online + in-person).

- Venue: McGill University, Montreal

- Date & Time: TBD June 2024

Chair: Dominique Marshall

- Description: Humanitarian agencies have long tackled questions of food (in)security. In doing so, they have largely contributed to contemporary conceptions of the causes and remedies of famines, to the making of a vocabulary around food security, and to the construction and the dissemination of the main representations of famine. This panel explores practices of famine relief at the village/micro level on three continents, by international and local agents. Furthermore, it discusses the convergence and divergence of ideas between humanitarian workers, about governance of food production and delivery, about healthcare and debility, and about climate and nature. The panel will compare how they leveraged these assumptions to accomplish their missions in four different micro-contexts.

Panelists:

- David Webster, Historian, Bishop’s University and Rogerio Savio Ma’averu, independent researcher, Timor-Leste, Famine, Aid and Strategies for Resilience in Timor-Leste Villages, 1975-79.

- Nassisse Solomon, Western University, “Village-to-Village”: Micro-initiatives with large-scale impact in Canadian Engagements with the Ethiopian Famine of 1984-88.

- Sonya de Laat, Research Associate, McMaster University, Dearth and Detail: Reviewing Historical Images for Greater Understanding of Causes and Responses to Food Security Crises.

- Machia Désiré, Enseignant permanent d’histoire-géographie-Education à la Citoyenneté et à la Morale, CES DE NKASSOMO /MINESEC, La diplomatie humanitaire suisse en Afrique centrale : dimensions locales, rétrospective et prospective.

- Interested in being a panelist? There is still an opportunity to join this panel. Please contact Dominique Marshall, DominiqueMarshall@CUNET.CARLETON.CA, by December 15 so that the panel can begin communicating about the round table in the New Year.

- The Annual meeting of the CNHH will take place during Congress which runs 12-21 June 2024. Details of when and where the meeting will take place, registration link, and an agenda will be shared closer to the date. It will be hybrid.

II. NEWS FROM MEMBERS

Dominique Marshall published “Teaching Human Rights History,” American Review of Canadian Studies, 53:1 (2023),118-130. She presented “The League of Red Cross Societies & Disabled People: Transnational insights on war impairment, capacity & debility”, Geneva, June 2023, Symposium on “The League of Red Cross Societies: Historical Perspectives 1919-1991”. The science portal of Gendered Design in STEAM, an initiative of the International Development Research Centre, which she co-directed, is now open: https://carleton.ca/gendesignsteam/ .

CNHH members Sonya de Laat and Nassisse Solomon have been collaborating with Arsenii Alenichev, as postdoctoral fellow at Oxford, on a project exploring historical legacies shaping contemporary visual representations of global health issues and activities. Alenichev recently published preliminary results of an exercise that aimed to explore the promise of generative AI to produce more ethical depictions than those that have been the subject of critique for the better part of the past several decades. Coinciding with the publication of an NPR piece about the project, de Laat (SdL) asked Alenichev (AA) about this experiment:

[SdL] What inspired the project?[AA] Since I started writing a PhD about precarious [clinical] trial subjects, Facebook started showing me the images of, like advertisements of young clinical trial [subjects], and they were smiling people and that was kind of very, very different from local realities, at least what I encountered in [west African country]… I interviewed trial subjects and many of them they were well really disturbed people because many of them there were ex-combatants, many of them just marginalized youth who participated in the trial for the money…That kind of prompted me to start asking questions about who created those images, how they’re created, why they are shown on Google in that way.

[The AI exercise] was a spontaneous kind of thing because my co-author really wanted to invert typical global health images. As I was trying to invert those images, I realized that it’s not really possible. I initially overlooked it and I remember I messaged [my co-author] just to say, “hey, we cannot do this exercise because it always tends to revert back to the suffering subject, the white saviour tropes.” [My co-author] was like, “Oh my God this is horrifying,” and then I was like, “oh, wait a second, yeah this is indeed horrifying because it actually tells quite a lot about the visual culture of global health and the kind of the relationship between artificial intelligence and chronic socioeconomic issues and the stereotypes and in ways in which they traveled.” And then I sent it to some friends and colleagues, some of them from the global south, and they were like, “it’s really horrifying.” It was quite striking that even if you ask AI specifically to produce images of black African doctors taking care of white kids, white suffering kids, it would always show you black kids as a recipient of care, and it would occasionally show you white doctors as providers of care. This really showcases the biases that whiteness is hegemonically coupled with the provision of care and blackness with reception of care.

[SdL] What is the main takeaway about generative AI in this instance?[AA] The whole harmful stereotypes that global health practitioners activists and scholars have been fighting against it just is being casually reproduced. The whole exercise makes me feel very uncomfortable because these images are problematic; I mean, those images were co-created, I participated in the creation of those images. I’m still deeply disturbed by the whole thing. But again those images they’re replicated from the matrix of quote-end-quote ‘real images’ and I think this is where the complexity lies primarily…

One thing that is crystal clear, that there is this biased one way another and we should actively resist the political, the contextualising notion that AI products are somehow neutral and value free. No, they’re the mirror of reality. We could employ people with global health heritage to kind of improve AI, to make sure that the data sets are more inclusive, but that, ultimately, is not going to fix the chronic systematic inequalities that are in the very fabric of our societies. So that’s one of the key takeaway messages. Yes, there should be more involvement of people from diverse backgrounds, but also, it’s a sign that our society is not OK.

Ultimately, this is a cautionary tale (again) about new technologies—this time it is photo-realistic generative AI and its inherent flaw of reflecting back biases and reinforcing societal prejudices rather than challenging or overcoming them. Even when actively trying to create counter-narratives, photo-realistic generative AI struggles and fails due to the existing historical record of images available on the Internet—which are predominantly reproductions of harmful stereotypes—that form the foundation of the software’s algorithms.

Possible means of remedying (or ameliorating) this situation include, as Alenichev suggested, involving or following the lead of people from diverse backgrounds in the creation of images. For historians, an option is to flood the net with a diversity of underrepresented or overlooked stories and with alternative representations to add more material for AI to draw from. Examples can be seen in the “Treasures of CIDA Photography Collections” or Chapters 9 of the Samaritan State Revisited.

Watch this space as Solomon, de Laat, and Alenichev build on the generative AI project with a parallel look at the historical record forming the visual foundations of images that generative AI draws from, and with continued discussions of promises and pitfalls of this technology.

More on the project and the full team that can be found here: https://www.oxjhubioethics.org/research/putting-people-and-diseases-into-the-picture

III. ARCHIVES NEWS

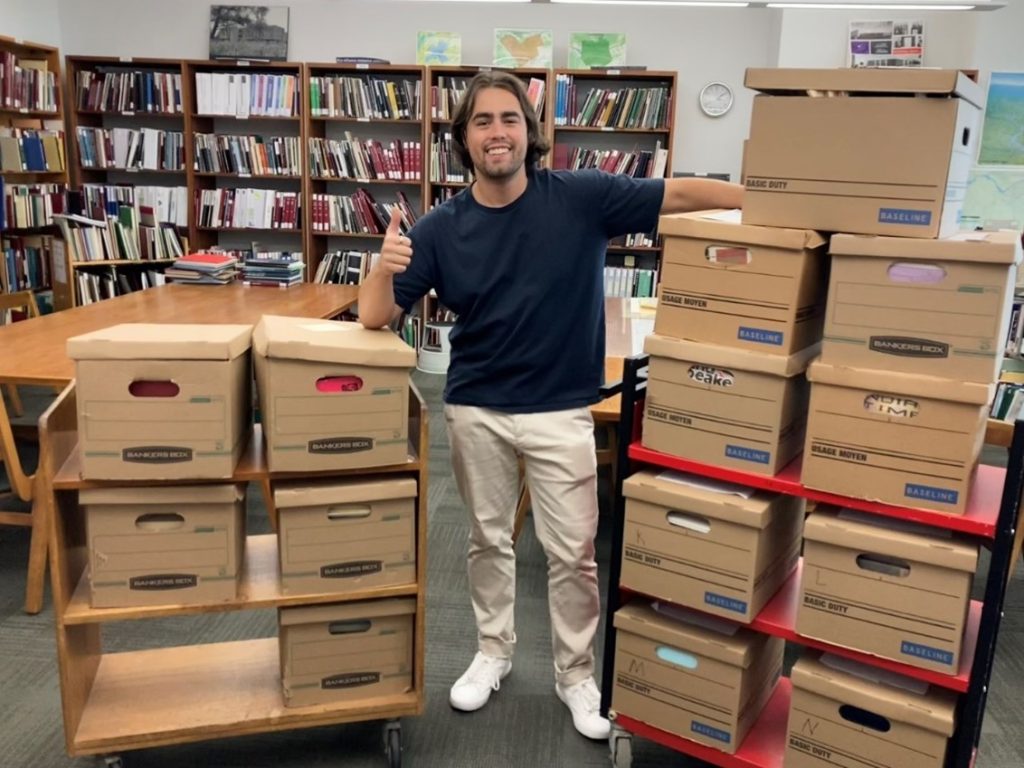

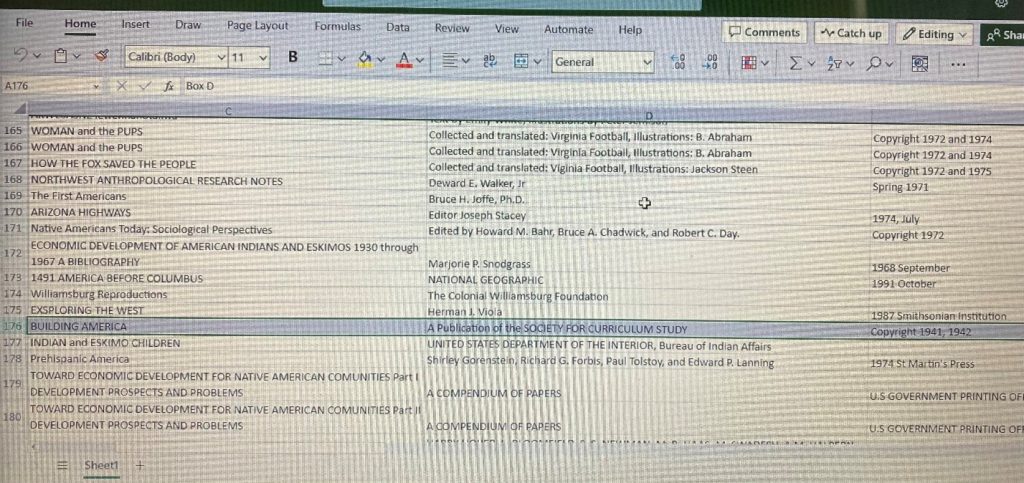

For the last three months, the Archival Rescue team based at Carleton University Archives and Special Collections (https://library.carleton.ca/asc) has been supporting the cataloguing of the library of the Native North American Travelling College (https://www.nnatc.org/). See the blog by Research Assistant Richard Marchese, on the CNHH website: https://aidhistory.ca/creating-an-archive-for-the-native-north-american-travelling-college-a-research-internship-completed-at-carleton-university/

IV. COMMON INITIATIVES FROM MEMBERS

- The new website of the Carleton University disability Research Group was launched in late October: https://carleton.ca/disability-research-group/ It includes exhibits sponsored by the CNHH:

- Transnational Representation: Canada and the Founding of Disabled People’s International, 1981 (https://transnationalrepresentation.omeka.net/exhibits/show/transnational-representation–/transnational-representation)

- Refugees, Disability and Technology in Transnational Postwar Canada, 1946-1953 (https://envisioningtechnologies.omeka.net/exhibits/show/refugees–disability-and-techn/an-unending-global-crisis)

- The 2013 edition of the CNHH Roundtable at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Historical Association at York University on “Ahistorical Aid: The Hidden Costs of Historical Amnesia in NGOs” was a great success. Thanks to convenor and chair Sarah Glassford, who is working at making its results public, to participants and CNHH mmbers, David Webster, Chris Trainor, and special guest Fabrice Weissman of the CRASH-msf project.

- The CNHH helped arrange the visiting fellowship of Ghanaian specialists of coastal fisheries Joseph Aggrey-Fynn (https://directory.ucc.edu.gh/p/joseph-aggrey-fynn) at Carleton University at the end of the Fall term 2023. Dr Fynn is involved in several transnational development project. The CNHH will post news of the activities surrounding his visits as soon as they are scheduled.

V. BLOGS & TALKS PUBLISHED BY THE CNHH SINCE THE LAST BULLETIN

CNHH Presents: Essential Reads in the History of Humanitarianism—Top 5 Resources on Humanitarianism, Development, and Photography, as recommended by Sonya de Laat.

Richard Marchese: “Creating an Archive for the Native North American Traveling College. A Research Internship Completed at Carleton University” (cross-posted from I-CUREUS blog) – early October.

CNHH Presents: Essential Reads in the History of Humanitarianism—Top 5 Reads on the History of Development, as recommended by Jill Campbell-Miller.

Contribute! If readers of the CNHH Bulletin would like to contribute to the “Essential Reads” series, or on any other subject relevant to our membership, please contact Sarah Glassford: Sarah.Glassford@uwindsor.ca . We would be thrilled to feature your reading recommendations, or your thoughts and experiences on other CNHH topics!

VI. WELCOME TO NEW MEMBERS

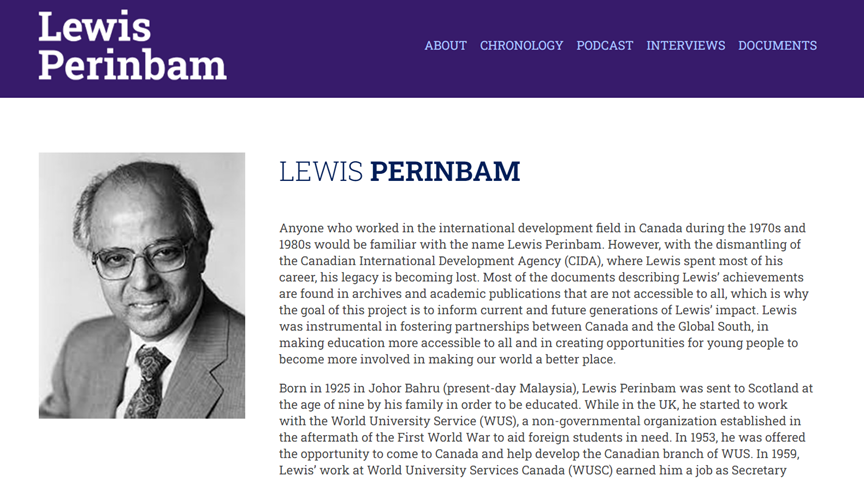

Anna Kozlova (2020-present) is a PhD candidate at the Department of History at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. She holds a BA in Communication Studies with a Minor in Law from Carleton University and an MA in World Heritage Studies from the Brandenburg University of Technology in Cottbus, Germany. Her research interests are focused on migration, diaspora, oral history, and transnationalism. She was the lead researcher on a MITACS-funded project “Two case studies in the public history of international development policies in Canada: the Lebanese Special Measures Program (1975-1990) and The Life of Lewis Perinbam (1925-2008),” which you can read about here.

The full list of members is on the CNHH website.

If you haven’t followed the CNHH on Twitter, please do so!

Feel free to tag us in your announcements, and we will retweet!

@AidHistoryCan

Sonya de Laat, Bulletin Editor

Copyright © 2023 Canadian Network on Humanitarian History, all rights reserved.