Envisioning Gratitude: Armenian Orphans in Canada

by Sandrine Murray

The Armenian Genocide was the result of the Ottoman government’s destruction of 1.5 million Armenians, most of them citizens within the empire. This was during and after the First World War. Most academics place the beginning of the genocide in 1915, though there are various accounts of violence against the Christian minority in the Ottoman empire before then. The Armenian Genocide is often seen as the first modern genocide, though to this day the term has been rejected by Turkey to describe what happened.

The Georgetown Boys were children refugees admitted to Canada between 1923 and 1927, thanks to the lobbying on behalf of the United Church of Canada and humanitarian groups. The Armenian Relief Association of Canada (ARAC) was central to petitioning the government to grant funds for 5,000 children to migrate to Canada. While initially choosing to send financial aid abroad instead of allowing the boys and girls into the country, the government eventually admitted them, under the understanding the children would be integrated and educated within proper British tradition. Most of the boys were placed on a collective farm in Southern Ontario, while the girls were sent to work in domestic settings with other families.

The use of photographs on behalf of the United Church of Canada in the context of the Georgetown Boys appears to reflect an overwhelmingly archival mindset when it comes to using photos in humanitarian contexts. For the most part, the photos are simple, individual or group shots staged in the same way a school group photo or family photo would be taken today. The images, taken in the later 1920s, seem to point to a period when photography was not central to promoting humanitarian efforts, which might be explained in part due to the lack of photographs in newspapers at the time.

In 1987, Canadian historian Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill, produced a short documentary on the Armenian boys welcomed to Canada after the genocide. Her own parents were survivors, and she spent most of her academic career focusing her research on the Armenian diaspora and immigration. The short documentary relies on the audio narration of the accounts of the boys and photography as the visual component. The story recounts their rough pasts, when they lost their families; their memories of home and what they once knew; and the daily struggles they faced in a new and foreign country. “All of us kids have had horrible experiences,” a young voice says. “My friend Sahad was only three when the genocide started. When the Armenians were massacred, he was really hurt, and they thought he was dead.”

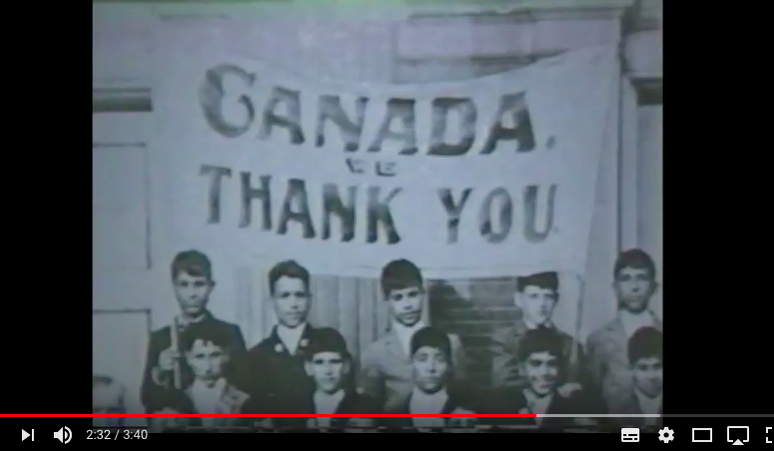

The Armenian relief Association of Canada brought over about 100 Armenian boys. Photos of the boys were taken by the United Church of Canada, and they are available on the church’s online digital collections. One particular photo displays a banner over a group of boys, which says, “Canada, we thank you.” Little insight or information is available on the nature or the occasion for which the photo was taken. It does however appear to be taken as a public declaration, designed to thank and to display gratitude, perhaps in a bid to shape public opinion positively.

In his paper, “The Cry of the Children: Accounting for the Entry of Child Survivors of the Armenian Genocide into Canada, 1880-1930” Daniel Ohanian examines the crucial role of campaigns on behalf of organizations like the Armenian Relief Association of Canada (ARAC) and the United Church of Canada. His work is a major research paper on Canadian immigration and church history in which religious, secular, and political interests intersect to engage individuals. It led government officials to break with established immigration policy to relocate child survivors of the Armenian Genocide to Canada. “I conclude that it was due to the strength of popular support raised, made possible by the wider contexts within which campaigns were run as well as the strategies of representation they employed, that led federal authorities to break with their restrictive immigration policy,” he writes.

It would be curious to see how the church and the ARAC’s lobbying may have differed had it been a few years later, when photography became much more significant within the promotion of humanitarian efforts, and its visual appeal drew people in a whole new way.

Still from the film The Georgetown Boys produced by Isabel Kaprielian, 1987. Available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2-QnVlIMME

Visual Disruption

The bulk of the photographs of the so-called Georgetown Boys are individual pictures of the boys, taken outdoors, in varying seasons, often with their arms crossed, and with large smiles on their faces. While the images conjure positive emotions, it is unclear from the pictures themselves what the full experiences were of these individuals once they arrived in Canada. Were they all put into happy, supportive environments? Did they receive the care necessary to mange the trauma they might have experienced before coming to Canada, and presumably were still having to deal with? Were some abused, exploited as farm labour? While most Canadians likely were sympathetic, did they face discrimination, did “Georgetown Boys” or “Armenian” take on a negative connotation in some circles?

There is much that photographs cannot show, that existed/exists beyond the frame of the image. It is important to consider these along with the positive elements that the photographs do depict and represent.

Finally, the photograph of “thanks” above: while it is often a sentiment that newcomers to Canada, particularly those who have struggled and lived through great hardships before coming to this country, such images have had the unintended effect of creating expectations of gratitude on the part of all newcomers; precluding newcomers from being able to be critical or make claims to rights and privileges. And opens to questions of when is a newcomer no longer a newcomer, when is a refugee no longer a refugee?

Sandrine is entering her fifth-year in journalism and history, after spending a semester abroad. In 2017 she was employed on an I-CUREUS/MDS/CNHH project and used the opportunity to do some research on the migrant crisis while on exchange in Trento, northern Italy.

This blog originally appeared as part of the Visual Histories of Canadian Aid to Refugees and Displaced People Abroad website and was funded by Migration & Diaspora Studies at Carleton University.

The image featured at the head of this blog comes from the Canadian Museum of Human Rights; “The Georgetown boys and girls” https://humanrights.ca/blog/georgetown-boys-and-girls

0 Comments

1 Pingback