By Sandrine Murray

- On the occasion of the celebrations of 40th anniversary of the Year of the Child, the Canadian Network on Humanitarian History used the archives of the Landon Pearson Resources Centre for the Study of Children and Children’s Rights (LPC) to prepare an exhibition on the report.

The United Nations proclaimed 1979 the International Year of the Child (IYC). Back then, television was the technology of the day, colour broadcasting introduced only a few years prior. No one could predict the arrival or impact of social media on children decades later. But how they viewed children’s rights at the time set a standard for today.

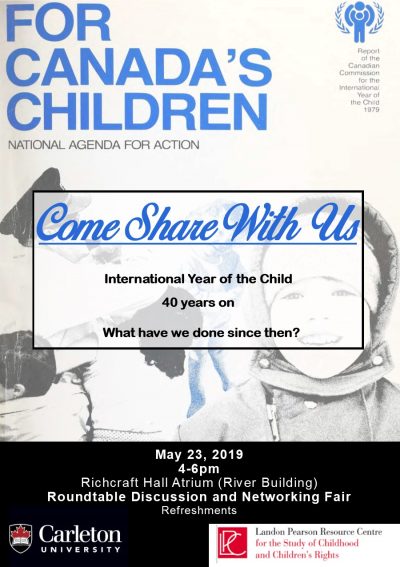

Following the UN proclamation, the Canadian government granted groups working for youth a million dollars for the year, a significant amount for the time. It was a big year for Landon Pearson. She was the vice-chair of the Canadian Commission of the IYC, tasked with allotting the money to different groups across Canada. A mother of five herself, she worked tirelessly for children’s rights and hasn’t stopped yet. Pearson and her team – mostly women—prepared a plan to action. The result was published in time for 1979, a document called For Canada’s Children. National Agenda For Action. (**)

Pearson ensured young people participated in the Commission’s work by insisting they meet with children and young people in every province in Canada throughout 1979. She took extensive notes on their concerns and perspectives, creating a strong legacy of involving children in policy discourse. Following the year of the child, every high level meeting included the participation of young people in her work in the Senate from 1994 to 2005. On May 23, during the 40th anniversary, three young people who spoke also reviewed some of the materials from the youth in 1979.

The Canadian Commission for the International Year of the Child was a bold agenda for children. On May 23, 2019 at Carleton University, Pearson discussed its legacy, alongside long-time friend and colleague the Honourable Monique Bégin, who was the Minister of Health and Welfare at the time, and representatives from government, health, advocacy, non-governmental and education sectors.

Their discussion sought to answer the following: Did the report make a difference?

“I was impressed with what we came up with,” said Pearson. Some of the recommendations were successfully applied; others are no longer relevant, and some were ignored. The section 43 of the Criminal Code, which allows force as means of correction, still hasn’t been scrapped as the report recommended. The document also did not foresee the current environmental crisis that would engulf modern-day discourse, and a conversation often led by younger people.

The videos below of the event include key moments from the discussion, as each advocate and leader discussed what they consider one advancement and one concern for children’s rights since the 1979 report.

Part one: Introduction

The impact of the report and Youth presenters: Sofia Henson Preibisch, Abigail Hatankaka and Alex Krneta (starts at 24:26 and continues in the first part of the second video)

Part two: The children speak, Monique Bégin, Judy Finley and Lisa Wolff

Monique Bégin (7:00)

Bégin is a long-time friend of Pearson’s. Her proudest achievement, which coincided with the 1979 year of the child, was the Child Tax Credit. It still exists today, albeit now under a different name.

Judy Finley (19:00)

Judy Finley is the graduate program director at the School of Child and Youth Care at Ryerson University. She’s worked in the field of child advocacy for decades. Her academic approach considers the parent-child conflict as the main reason for accessing welfare. One of the advancements she noted since the report was that of children’s rights as it relates to education.

Lisa Wolff, Unicef Canada. (24:22)

She was particularly struck by the foresight included in the 1979 report, and what has changed (such as the absence of a vaccine card).

Part three: Rachel Gouin, Brittany Matthews, Sara MacNaull, Jennifer Christie and Louise Hanvey

Rachel Gouin, Child Welfare League (en français)

She notes the 1979 report reflects an understanding of mental health and addiction differently, because there wasn’t as much research or information on the topic as there is now.

Brittany Matthews, Caring Society (first nations children)

Brittany Matthews said the report is still relevant for 160,000 indigenous children of today. (6:45)

Sara MacNaull, The Vanier Institute for the Family, (11:00)

The language used to describe family breakdown and chaos, or in particular, ”unmarried, adolescent mothers,” struck MacNaull. She noted how the definition of a family has broadened. Now there’s a much greater respect for diversity in family patterns, she argues citing common-law couples, same-sex and foster children as examples.

Jennifer Christie, 4-H Canada (18:00)

4-H Canada is a youth organization for those in rural contexts. Christie herself was raised in a farm family, so the organization is close to her heart. She says her organization is as relevant as ever to reach children in under-reached communities. To continue on this path, it needs to ensure it’s backed up by data.

Louise Hanvey, Children’s Health (22:00)

Infant mortality rates are a third of what they were back in 1979, says Hanvey. “We take really good care of babies who are born too soon in Canada now,” she says. Women access prenatal care much more readily than before. The percentage of death due to preventable injuries in children and youth has also gone down 70 per cent in 40 years. Things that are legislative and regulatory help with such matters. Hanvey points to safer cribs and playgrounds as a reflection of careful policy. But inequalities remain, especially for Indigenous children and poorer neighbourhoods.

Part four: Paula Kingston

Paula Kingston, Lawyer, Senior Counsel (Retired), Justice Canada.

Kingston adressed the youth criminal justice system and the historical legacy of the deprivation of liberty. She notes many Canadians might not know their country locked up more young people than any other Western country for a number of years. Depriving young people of liberty, like residential schools and the Young Offenders Act was a way for the Canadian government to deal with social issues.We now have an act to change that, she explains, and it’s been very effective.Back in 1979, promiscuous girls could be sent to jail until they were 21. It wasn’t a crime, but it was a way for the justice system to deal with certain social problems. The change in approach came after the International Year of the Child, the biggest of which was The Youth Criminal Justice Act, which Pearson sponsored when it was presented in the Senate.

(*) Sandrine Murray received a Bachelor Degree in Journalism and History in 2019. She also helped prepare the exhibition for the anniversary.