by Mike Molloy

Produced 14 years ago, and printed in only a few dozen copies for friends and colleagues, the memoirs of one the main actors of Canada’s actions towards displaced persons between 1945 and 1980 is now available widely, thanks to the digitization services of the MacOdrum Library. His long time co-worker Mike Molloy reviews the book for a joint blog with the Canadian Immigration Historical Society; the illustrations come from his collection.

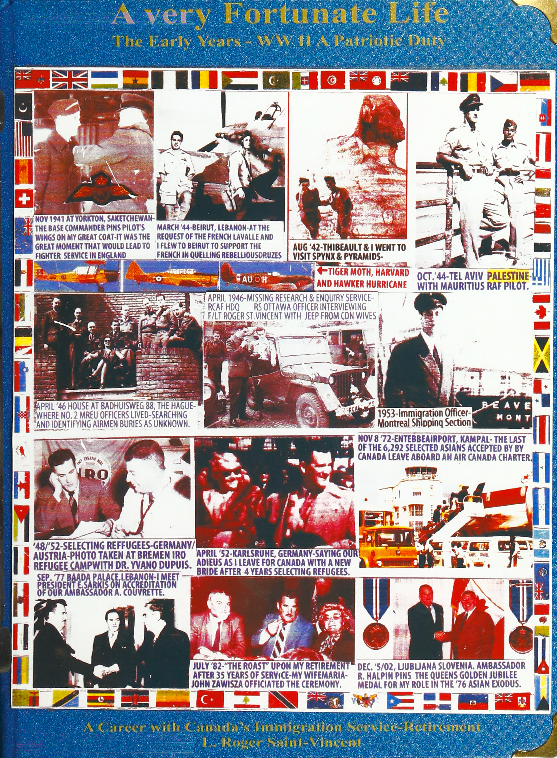

A recent addition to Carleton’s online holdings is an unusual self-published autobiography by Roger St. Vincent, World War Two fighter pilot and long serving member of Canada’s immigration foreign service. Regarding the inclusion of the word “very” in the title, Mr. St. Vincent recently explained “The title A very Fortunate Life stemmed from having survived a terrible [airplane] crash during the war and having a loaded rifle aimed at my head returning from a trip to the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” It bespeaks an unusual and interesting life and career.

What makes this book so unusual is the level of detail Roger St. Vincent was able to recall when he pieced together his life’s stories after taking a computer course in his 70s. It begins with his recollections of childhood (born in 1922) in a large, loving and very poor, 12 person Montreal working class family where he grew up sharing a bed with two brothers. As a child he was fascinated with flight and recalls the 1933 visit to Montreal of a squadron of Italian airplanes and seeing British and German airships.

The war broke out as he finished high school. Unable to find a job, with his parents’ permission, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) – he liked the light blue uniform – and was trained as a pilot in Ontario and Saskatchewan under the Commonwealth Air Training Plan (CATP) before shipping out to the UK in December 1941. Like every other part of the book, the section on his training and subsequent war time experience which took him to Britain, Ghana, North Africa, Cyprus and the Middle East, is lavishly illustrated with unique personal photos, maps, documents, ephemera related to the details of his daily life, his comrades, and acquaintances against the backdrop of struggle to contain and defeat the Axis forces in North Africa.

St. Vincent was initially assigned to #1 Aircraft Delivery Unit, a group that flew Hurricane fighters and light bombers from assembly points in Ghana, West Africa, across the continent from Sekundi Takoradi in Ghana to Cairo via Kano (Nigeria), Fort Lami (Chad), El Fasher, El Geneina, El Obeid, Omdurman, Wadi Halfa and finally to Cairo. Anyone with an interest in World War Two will find the account of his wartime career, observations and comment about being a francophone member of the RCAF serving, as did so many Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, with the British Royal Air Force. Accounts of his varied assignments, like providing air support for the liberation of Lebanon are fascinating as is his assertion that, thanks to the Commonwealth Air training Plan, there were always many more trained pilots available than airplanes for them to fly.

A Flight Lieutenant by the end of the war, Mr. St. Vincent remained with the RCAF and returned to Europe with the Missing Research and Enquiry Service where he was responsible for tracking down the resting places of “unknown” Canadians shot down during war.

On returning to Canada he joined the Immigration Department, serving at the Lacolle port of entry, south of Montreal. When Prime Minister Mackenzie King announced Canada would begin resettling people from the displaced refugee camps in Western Europe, St. Vincent joined the Canadian Government Immigration Mission,(CGIM) stationed at Karlesruhe Germany. For the immigration historian, his account of CGIM activities in occupied Germany, Austria and in Italy is a gold mine of information. It is the only firsthand account of the operation that brought 163,000 “DPs” (Displaced Persons) including, Jewish orphans, Mennonites, and others swept up by the war and unwilling to return home to the Soviet Union and communist Eastern Europe. It was at this time that another reason for the “very Fortunate” book title occurred: he met, wooed and married the love of his life, the beautiful Marija Luisa Schultz.

Roger and Marija returned to Canada from 1952 to 1957 during which time he drew on his veterans benefits to build their house, and where his service included receiving and resettling Hungarian refugees. Following this he was assigned to the Rome immigration office (1957-61.) It is at this time that one can observe his development as a manager, improving procedures and speeding up processing, for which he received an award.

Other assignments followed: Paris 1963-64, Rome again 1964-67 (during which time he was involved in testing the proposed “point system” for the nominated relative category, later to become the norm of Canadian immigration practices) and Jamaica where he was responsible for immigration from the Caribbean and Central America. I met him for the first time during this period. As a trainee I was sent to Vienna just as the Russians crushed the Prague Spring. Roger, then vacationing in Vienna, turned up at the Canadian visa office and was put to work booking refugees on Canada bound charters and getting them to the airport and onto the flights. Another trainee and I, working out of a broom closet, reviewed the files for completeness and signed the visas before handing them off to Roger, and I decided I’d work with him if the chance came up.

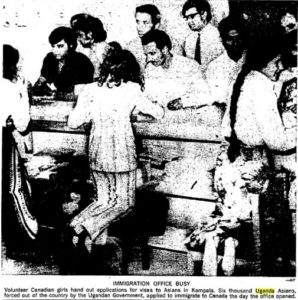

Day 1. The visa typists handing out applications:The hard working friendly young women established the teams brand. Ginette Leroux, Jolene Carriere and Mary Ellen Hemple.

That chance came up three years later, in 1971, when I was posted from Japan to Lebanon where St. Vincent managed a small team of officers providing immigration services to 38 countries from Iran to Zambia. Shortly after I arrived, he assigned me to make an “area visit” to interview applicants in Kenya, Zambia, Mauritius, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia. I made this circuit twice in the next five months. We had no applications from Uganda, but Idi Amin had just ousted the elected Ugandan leader. St. Vincent believed trouble was coming and asked me to spend a few days in Kampala during each trip, getting to know the friendly embassies, meeting the leaders of the small but influential Asian community and assessing the situation.

Presenting the first UGX (Uganda Program) visa. Roger St. Vincent; recipient of first visa, Visa Typist Jolene Carrier, Mike Molloy

I had just returned from the second trip when Amin gave the Asians 90 days to depart, and I soon found myself in Kampala as St. Vincent’s assistant with a team of immigration officers and staff, doctors and military medical technicians tasked with moving 6,000 people in eight weeks to Canada. (Check out www.carleton.ca/uganda-collection for details.) In the midst of chaos St. Vincent’s calm leadership, self-confidence and compassion set the tone for the rest of us and we got the job done with efficiency and style. In those days I never saw him without a black notebook under his arm and it transpired that he kept detailed, hour by hour, notes on everything we and he encountered.

Within the year St. Vincent used the notes to create an account of the Uganda Asian operation he called “Seven Crested Cranes” which was published by the Canadian Immigration Historical Society. There is nothing like it in the literature of Canadian immigration history – meticulous, candid and deeply personal. Happily “Seven Crested Cranes” along with ancillary and subsequent material makes up Chapter 10 of A very Fortunate Life. The experience the young officers who served in Kampala gained under St. Vincent’s leadership would prove very useful when the Indochinese refugee crisis broke 7 years later.

Following the Ugandan episode St. Vincent served for three years as Immigration Coordinator for the Montreal Olympics, a serious responsibility in the wake of the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics (which, incidentally, occurred while we were Kampala.)

With the civil war in Lebanon, Canada had established a special program for relatives of Lebanese Canadians affected by the war. Violence in Beirut had resulted in the immigration staff being transferred to Limassol, Cyprus. St. Vincent took over management of the Limassol operation in January 1977, oversaw the reopening of the embassy in Beirut and managed the embassy as chargé d’affaires in a period characterized by serious violence, including the killing of the ambassador’s driver.

The book goes on to describe his final overseas assignment in Yugoslavia (1979-81) along with his final two years 1981-82 with the immigration program as Director Immigration Operations, Western Europe at External Affairs. He retired in 1982 to take care of his wife, Marija.

This book will be of interest to those concerned with World War Two, the RCAF, the North African Campaign, immediate post WW2 immigration history, the Displaced People, post war immigration and refugee policies and practices, the Hungarian, Czech and Ugandan refugee movements, changing immigration administration, attitudes policies and practices and joys and travails of life in the immigration component of Canada’s foreign service. It contains copies of some hard to find documents including the 1947 Department of Mines and Resources “Procedures for Handling Alien Immigration.”

Cartoon from the Edmonton Journal stapled to a fragment of the Demand Guide in Use in fall 1972 ( Political correctness had not yet been invented).

Entirely self-written and self- edited, “A very Fortunate Life” is occasionally a bit quirky and the index will always get you close, but sometimes you have to hunt around a bit. With its hundreds of photos, documents and images, it is an enjoyable read and a unique source of insights and information on the delivery of Canada’s immigration program, and the people who delivered it between 1947 and 1982.

Mike Molloy

Adjunct Research Professor

Department of History

Carleton University

Direct link to PDF: http://oaresource.library.carleton.ca/history/A_Very_Fortunate_Life.pdf

Link to catalogue record: https://catalogue.library.carleton.ca/record=b4738239

We thank George Duimovich, Associate University Librarian — Collections and Technology at the MacOdrum Library, for overseeing the digitization of the rare book.

Guy Cuerrier left me a copy of documents and background information concerning the REFUGEE STATUS ADVISORY COMMITTEE [RSAC], the 1981 RSAC determination process and a 1978 UNHCR handbook from the RSAC.

I would forward these to anyone interested or to the McOrdrum Library if appropriate.

Guy Cuerrier left me a copy of documents and background information concerning the REFUGEE STATUS ADVISORY COMMITTEE [RSAC], the 1981 RSAC determination process and a 1978 UNHCR handbook from the RSAC.

I would forward these to anyone interested or to the MacOdrum Library if appropriate.

Mike

Hello

Hope you are well

Am planning to write book on Uganda expulsions early next year and would like to feature your outstanding work

Can we connect ?

Are you on what’s App

My U.K. number is 44 7913 803435

Justvto refersh your memory I am Ishrath Velshis uncle . Mila’s Brother .

I met you in Ottawa about 13 years ago and you very kindly introduced me to Roger St Vincent .

Keep well Mike and do try and connect

Mohamed Keshavjee